It was the week when tickets for a summer Oasis concert at Manchester City’s stadium went on sale at a price of £32.50 and the local council was so hard up that it considered ditching the deteriorating, 80ft inflatable Santa who always perched on the town hall roof. A time, 20 years ago, when Manchester seemed to be struggling as much as its two football teams, who met at Old Trafford on the first Sunday in November.

United were eighth – reeling from a 2-0 loss at Portsmouth the previous week and Roy Keane’s dark pronouncements about their declining standards. City were 13th, recently beaten in the League Cup by Arsenal’s third team and led by Kevin Keegan, who was the bookies’ 13-8 favourite to be the next boss sacked.

The odds against Pep Guardiola leaving City were 33-1 on Friday, despite a stunning run of seven defeats in ten games, and the club published financial results revealing Premier League record revenues of £715million and a £73.8m profit. Not quite the crisis Keegan knew at club carrying £62million in debt.

But the two Manchester sides’ ‘combined position’ of 17th going into this weekend – United 13th this time and City fourth – is the worst since that drab, stone cold Stretford day in November 2004, when their positions added up to 21. And though some of the playing personnel from back then – Gabriel Heinze and Alan Smith in red, 19-year-old Willo Flood and Ali Benarbia in blue – make it seem a different universe, there are distinct parallels.

Then, as now, there were signs of the empire crumbling – Ferguson’s – and then, as now, the club who had spent years in that empire’s shadow were unable to capitalise. Keegan’s mood matched the dark nights on that weekend, when the clocks went back, and the story of City’s shirt sponsorship deal with a firm called ‘First Advice’ seemed like a metaphor. Shirts were printed, team pictures were taken – and then the firm went bust.

Though no-one saw or knew it, the foundations of the modern City were actually being laid at that time. The club had just moved into what was then called the City of Manchester Stadium – built for the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

The last time Manchester United and Manchester City met with a ‘combined position’ lower than on Sunday was in November 2004

Sir Alex Ferguson looked to be coming to the end of his time with the Red Devils, who had fallen behind rivals Arsenal and Chelsea

Pep Guardiola has had similar struggles this term, with his team well off the pace in the Premier League and uncertain of their European qualification following one win in their last 10 games

The £110million facility, given to the club for virtually nothing, was a significant reason why Abu Dhabi chose to buy City, rather than Everton or Newcastle United, as it used sport to win friends and influence in 2008. But back then, the stadium was just a bland, breeze block structure, with a ‘Manchester City Experience’ museum upstairs and a huge banner in the East Stand, declaring that the spirit of the old Maine Road Kippax ‘will never die.’

United’s struggles were the big story on that November weekend. It was the 18th anniversary of Ferguson’s arrival at Old Trafford and the troublesome early years of his reign aside, he was facing up to the most difficult period of his time at United, with Chelsea soaring, a year after Roman Abramovich’s arrival, under Jose Mourinho, whose first five months had been sensational.

The disastrous result at Portsmouth had left United nine points adrift of Arsenal and Chelsea and Ferguson admitting that, as a 62-year-old about to turn 63 with a pacemaker recently fitted, one thing which could not be ‘guaranteed’ was his health. He insisted at his pre-match press conference that weekend that there would be no compromises from him, but the one-year rolling contract he’d signed allowed him to disguise his departure date.

Perhaps, Ferguson inferred, he would be out of the place before his investment in Wayne Rooney, signed from Everton six weeks before the derby, and Cristiano Ronaldo, who had arrived the previous year, bore fruit. Rooney had still started only four United league games by then.

‘What I want to know when I do leave is that I’ve done my best and have not slackened off. In other words, not given someone else the headaches and problems to solve,’ Ferguson said. ‘I want to see the development of a lot of the young players here. If they haven’t reached their peak when they leave that doesn’t matter to me. Manchester United come first and everyone else second.’

Always a good man for a crisis, he displayed good humour at that press conference. When United’s 5-1 defeat to City in September 1989 was mentioned, he placed his head on the table in mock despair.

A very different picture has emerged this week from Manchester’s current preeminent manager. Pep Guardiola’s remarkable interview for the Spanish Desmontadito podcast inferred that he is beginning to lose his appetite for the infernal weekly struggle of club management. In that candid conversation with Spanish chef Dani Garcia, Guardiola visualised a world beyond Manchester City, of cooking, golf and managing to sleep. In a subsequent interview with former Italy international Luca Toni before Wednesday’s Champions League defeat by Juventus, he said his state of mind was ‘ugly’, that his sleep was ‘worse’ and he was eating more lightly as his digestion had suffered.

He struck a more upbeat different tone at his press conference on Friday– arms folded resolutely, less clutching at his head than usual and absolutely none of irritation with the questions which he can sometimes display on such occasions. ‘I’m fine. I’m very conscious about what happens next.

United were in lowly 8th place, while City, before the Abu Dhabi takeover, sat in 13th ahead of their 2004 clash

Ruben Amorim will be looking to get the better of Guardiola for the second time in two months

Amorim admitted that the two sides are not coming into the fixture at their level expected

What I can do,’ he said, when asked about that very personal sense of his own struggle which he had poured out. ’In our jobs we always want to do our best or the best as possible. When that doesn’t happen you are more uncomfortable. Move forward, keep working, do what you have to do. The problem is the bad moments, not me. We are fine. I am fine.’

Yet he still conveyed a sense of raw emotion and melancholy; a sense that his players, some of them injured and with a fixture schedule which is far too onerous, are somehow the tragic victims in what has befallen the club these past few months. ‘The soul and spirit are there but we are sad,’ he said. ‘It’s time to survive. Survive. Stay there. Be close than ever.’

There is always a gap between reality and what a manager says in the public domain. Too much can be read into these events. But the sense of powerlessness – a football club now at the mercy of events – which Guardiola conveyed was not convincing. Ferguson under pressure this was most certainly not.

As he headed into his first Manchester derby, Guardiola’s opposite number Ruben Amorim hinted that he sees how far the fixture has fallen from the clash between two giant, self-confident sides that it really ought to be. ‘It should be like two great teams fighting for the title, and it is not that in this moment,’ he said. ‘I just want to improve the team so I can treat it like a normal derby.’

Yet he also seemed acutely aware of the way that football can turn on you, punish hubris and over-confidence. He was desperate to wave away any talk of his Sporting Lisbon team beating Guardiola’s side 4-1 in a Champions League home tie on home soil last month.

‘No, no, no, no,’ he responded, when ask if he was facing a weakened City side. ‘The great teams can respond in any moment, and I think they are in a better place than us in the type of understanding the game – the way they play, the confidence they have. Even in these kind of moments. We have a lot to focus on in our team. Of course we have a strategy to try to win the game with the strategy like it should be, but we are focused just on our team.’

Ferguson’s approach to adversity – so different to Guardiola’s – was illustrated out on that weekend in 2004. ‘He always knew what he would communicate before he walked into the press room to talk and he would always be at his best at a time of difficulty,’ says one United executive from that time.

‘He’d be circling the wagons, working out how to turn that press conference to his advantage. He’d know the anniversary was bound to throw up questions about his future. The message was, ‘I’m here for the foreseeable. I’m sorting this out.’

A then-19 year-old Wayne Rooney shone after coming on as a substitute against United’s bitter rivals 20 years ago

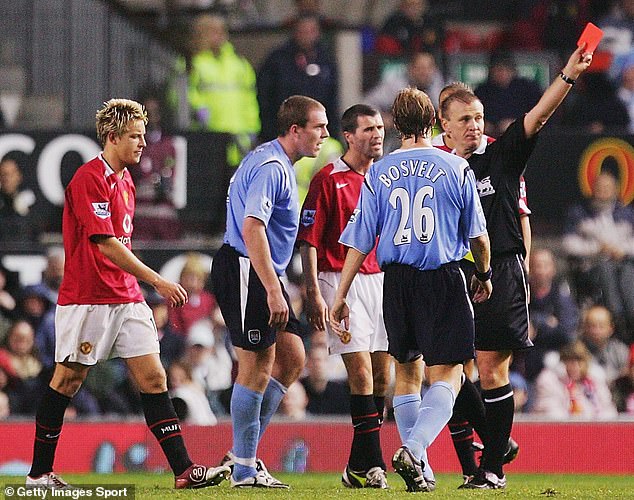

City left Old Trafford with a point after withstanding the United barrage to secure a draw

The mood among United fans that weekend was mixed, with the future ownership of the club up in the air after Ferguson’s spectacular fall-out with shareholders John Magnier and JP McManus that year threatening to open the door to the Glazers’ ownership.

‘The ownership of the club was a concern for everyone,’ says Andrew Longden, one of those at the game. ‘It was obvious that Rooney and Ronaldo were going to be stars but no one knew how long that would take. Keane didn’t seem happy, Paul Scholes hadn’t scored for months and goals had dried up.’

City fans approached the derby with gallows humour. ‘We had Robbie Fowler and Steve McManaman. They had Ruud Van Nistelrooy, Alan Smith, Rooney and Louis Saha,’ says Jake Bowerton, one of their fans that day. ‘And they had a banner on the Stretford End, counting out the years since our last major trophy. It was 30 by then. ’Ferguson treated with disdain a suggestion at his press conference that 29-year-old Scholes, who had not scored in eight months, had lost some of his sparkle.

Scholes bore out his manager’s assessment when the game started, despatching a sublime 60-yard ball for Saha who ran in behind and clipped beyond the onrushing David James. Keegan’s 22-year-old left-back Stephen Jordan, in only his second start for City, sprinted back from the edge of the six-yard box to hook the ball off the line.

City sweat blood to keep United out. The few stardust moments came from the 19-year-old Ronaldo. The genius moment came from Rooney, a substitute, also aged 19, who dragged the ball under his studs to manoeuvre it past Distin and shaped to shoot. Richard Dunne, man of the match, got the block in. The game was a goalless draw – the 12th time United had failed to score that season and somehow an emblem of the two clubs’ collective impotence.

There would be more struggles ahead. He could not rein in Chelsea, who won that season’s league title with 95 points, 18 more than third-placed United. And then, the following season, came the club’s annus horribilus. Chelsea retaining the title and United crashing out of the Champions League at the group stage.

The tougher the terrain, the more determined Ferguson seemed to be to take it on. ‘It might be because of my Glasgow upbringing or because of my working class roots,’ he later said. ‘That’s for the psychoanalysts to decide.’

The talents of those two 19-year-olds, Rooney and Ronaldo, did bear fruit and by the 2006/7 season, which many anticipated being Ferguson’s last, he had wrested back the title from Chelsea.

The scale of Amorim’s task to transform Man United into title challengers has been revealed in the last month

Manchester City have looked a shadow of their former selves this season and they head into the derby off the back of a 2-0 defeat against Juventus in midweek

City, who appointed Stuart Pearce to succeed Keegan in March 2005, eventually entered their new world under Abu Dhabi ownership – a challenge Ferguson, a force of nature the age of 67, felt irresistible. ‘I just considered it another in a long line of challenges with which we’ve had to contend,’ he said.

Now it is the 39-year-old Ruben Amorim seeking to seize for United the opportunity presented by City’s struggles. He is is contending with some of the same chaos that Keegan found at City, with resources limited because of financial sustainability rules.

It may mean the sale of players like Marcus Rashford – who as a seven-year-old in 2004 was at Fletcher Moss Rangers in south Manchester, weighing up whether to go to United after training at City, with Liverpool and Everton also in the hunt for him.

Twenty years on from that last low point, Santa is in his customary position on Manchester town hall roof and the cost of concert tickets – as much as £600 to see Paul McCartney at the new Coop Live venue near the Etihad on Saturday – are the talk of the city. And now, just like then, the red and blue halves of Manchester are holding their breath, waiting to see what happens next.

This article was originally published by a www.dailymail.co.uk . Read the Original article here. .